The use of torture, or “abuse” of prisoners is easily condemned on moral grounds. It violates the very basic rights of being human and therefore disgusts most of us. However, torture as an information gathering method is as ancient as it is nasty, and have on many occations proved useful in times of war and crisis – even by the good guys! To simply denounce it is therefore a mistake as it fails to address a harsh reality as well as the moral fact that the ends will sometimes always justify the means. If the survival of mankind, or an entire state, is at stake, there are many of us who would be willing to look away while our national security agencies are “roughing up” potential information holders. However, the almost impossible question is where the line should be drawn. What ends are important enough to justify crimes against humans rights? The answer is, and always will be, a completely subjective interpretation.

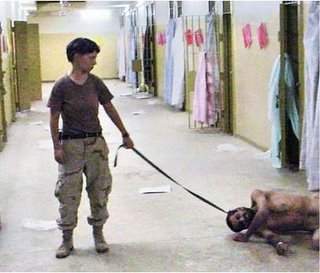

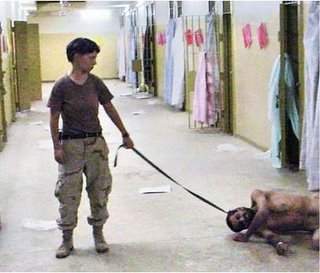

The use of torture, or “abuse” of prisoners is easily condemned on moral grounds. It violates the very basic rights of being human and therefore disgusts most of us. However, torture as an information gathering method is as ancient as it is nasty, and have on many occations proved useful in times of war and crisis – even by the good guys! To simply denounce it is therefore a mistake as it fails to address a harsh reality as well as the moral fact that the ends will sometimes always justify the means. If the survival of mankind, or an entire state, is at stake, there are many of us who would be willing to look away while our national security agencies are “roughing up” potential information holders. However, the almost impossible question is where the line should be drawn. What ends are important enough to justify crimes against humans rights? The answer is, and always will be, a completely subjective interpretation. Let us bring this difficult debate to the current war on terrorism and the ongoing campaign in Iraq. From an international perspective, it seems clear that the US government has crossed the line. But within the US it seems as if public opinion is at least divided on the issue. A decision based on morals alone is therefore perhaps too subjective to be useful. With the risk of being called a cold hearted bastard, I would therefore like to add the purely pragmatic variable of strategy to the debate on torture.

A problem of the War on terrorism and the campaign in Iraq is that these campaigns are supposed to protect liberal democratic ideals. The use of torture is therefore seems to contradict the very purpose of the wars. How undemocratic and disrespectful of human rights can you be in a campaign that serves to protect the very same ideals?

With this problem in mind, we should ask ourselves, to what extent does the methods used in the campaign support or obstruct the achievement of the aims of the campaign? In Iraq the US-led coalition seems to shoot itself in the foot by employing rough methods. It is virtually impossible to convince the Iraqi people and world opinion of your good intentions when employing certain methods. The effects of these methods are therefore loss of strategic credibility and lost battles for the hearts and minds of the Iraqi people – something that is hugely important for success. Considering that the use of torture as a method is a crime against human rights, as well as a cause of enormous losses in terms of strategic aims, one can only wonder what type of information could be obtained from the tortured detainees. Could an insurgent ever hold information that would be important enough to employ torture as a method? It seems unlikely!

In the war on terrorism it seems theoretically possible, although quite unlikely, that a detainee might have information important enough to justify torture. In this case we are of course talking about information such as direct knowledge of where and when weapons of mass destruction would be used by terrorists. However, the enormous loss of credibility as a force for good that the US is experiencing at the moment should be evidence enough that torture will never be justifiable in a cost-benefit analysis.

Since the moral arguments against torture do not seem to be enough to stop even the most liberal democracies from employing it as a method in war and crisis, I hereby present strategy as an equally potent reason to abolish the use of torture. From a pure cost benefit perspective I would therefore strongly recommend the governments employing these methods to stop. Torture is a sure way to lose the war in Iraq as well as the war on terrorism.

(c) Robert Egnell

The use of torture, or “abuse” of prisoners is easily condemned on moral grounds. It violates the very basic rights of being human and therefore disgusts most of us. However, torture as an information gathering method is as ancient as it is nasty, and have on many occations proved useful in times of war and crisis – even by the good guys! To simply denounce it is therefore a mistake as it fails to address a harsh reality as well as the moral fact that the ends will sometimes always justify the means. If the survival of mankind, or an entire state, is at stake, there are many of us who would be willing to look away while our national security agencies are “roughing up” potential information holders. However, the almost impossible question is where the line should be drawn. What ends are important enough to justify crimes against humans rights? The answer is, and always will be, a completely subjective interpretation.

The use of torture, or “abuse” of prisoners is easily condemned on moral grounds. It violates the very basic rights of being human and therefore disgusts most of us. However, torture as an information gathering method is as ancient as it is nasty, and have on many occations proved useful in times of war and crisis – even by the good guys! To simply denounce it is therefore a mistake as it fails to address a harsh reality as well as the moral fact that the ends will sometimes always justify the means. If the survival of mankind, or an entire state, is at stake, there are many of us who would be willing to look away while our national security agencies are “roughing up” potential information holders. However, the almost impossible question is where the line should be drawn. What ends are important enough to justify crimes against humans rights? The answer is, and always will be, a completely subjective interpretation.

3 Comments:

You're a cold-hearted bastard; and I thank you for that. Of course I'm sure you're not cold-hearted, your willingness to inhabit that mental territory requires courage. And from that perspective you offer some clarity to this important discussion.

As an American, I know that you are correct in your judgment that Americans are divided on the issue of torture--much to my horror.

To a great extent "pragmatism" is understood here as "practical." But your post shows that there is a much deeper understanding. Louis Menand in his book "The Metaphysical Club" discussed how pragmatism fell out of favor. The Cold War was proposed in opposition of Good vs. Evil,even Dr. King and the Civil Rights movement too. Such is the way the conflict in Iraq is being sold today.

Modern concepts of Human Rights do not grow out of such a Manichaean perspective, even as the language here is "endowed by the Creator."

A more humane vision of world affairs is possible through the more "ecological" perspective of pragmatism. But such a perspective is unfamiliar to most Americans today.

It's an interesting one that, I find, is very well dealt with by Michael Walzer. In this interview (http://eis.bris.ac.uk/~plcdib/imprints/michaelwalzerinterview.html), he makes the following argument:

"One of my examples was the 'ticking bomb' case, where a captured terrorist knows, but refuses to reveal, the location of a bomb that is timed to go off soon in a school building. I argued that a political leader in such a case might be bound to order the torture of the prisoner, but that we should regard this as a moral paradox, where the right thing to do was also wrong. The leader would have to bear the guilt and opprobrium of the wrongful act he had ordered, and we should want leaders who were prepared both to give the order and to bear the guilt. This was widely criticised at the time as an incoherent position, and the article has been frequently reprinted, most often, I think, as an example of philosophical incoherence. But I am inclined to think that the moral world is much less tidy than most moral philosophers are prepared to admit. Now Dershowitz has cited my argument in his defence of torture in extreme cases (though he insists on a judicial warrant before anything at all can be done to the prisoner).

But extreme cases make bad law. Yes, I would do whatever was necessary to extract information in the ticking bomb case - that is, I would make the same argument after 9/11 that I made 30 years before. But I don't want to generalise from cases like that; I don't want to rewrite the rule against torture to incorporate this exception. Rules are rules, and exceptions are exceptions. I want political leaders to accept the rule, to understand its reasons, even to internalise it. I also want them to be smart enough to know when to break it. And finally, because they believe in the rule, I want them to feel guilty about breaking it - which is the only guarantee they can offer us that they won't break it too often."

One should note, however, that in the hypothetical example, the 'supreme emergency' used to justify torture is a bomb in a school - hardly an existential threat. I don't know whether this signals a change of heart from Walzer.

David, London

Thank you very much for your comments! This type of informed discussion is really the reason for writing! Anyway Kaunda, I will have to look at Menand since I often seem to fall back on a form of human pragmatism. I would further like to hear more about "ecological pragmatism".

Anonymous, Walzers discussion on supreme emergencies again shows the difficulty of drawing the line of moral justification. Supreme emergency as an existential threat is easy, but as you rightly point out, the school example is very hard and might signal a shift in Walzer's thinking. How many kids have to be in the school to justify torture. 5? 50? Not the kind of decisions we like making...

/Robert

Post a Comment

<< Home